Canadian Vet Practice, published since January 2006, provides continuing education to the veterinary profession in Canada through coverage of both national and international veterinary conferences. Written with the busy practitioner in mind, each bimonthly issue offers news, relevant and practical clinical and practice management information, as presented by leading experts. All articles are veterinarian reviewed and approved prior to publication.

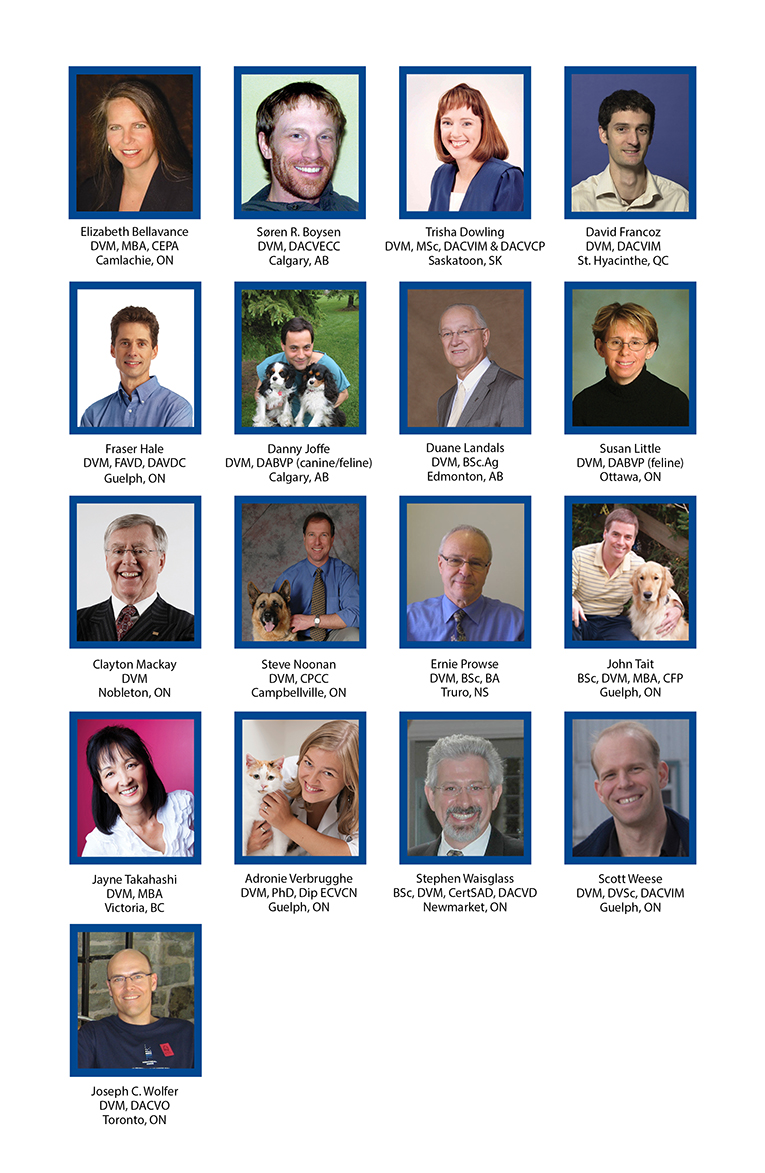

Advisory Board Members

Canadian Vet Practice is supported by an advisory panel of esteemed Canadian veterinarians.

Editorial

Canadian Vet Practice is unique in that it keeps Canadian veterinarians informed about the latest companion animal, livestock, equine, avian, exotic and other animal species health issues. Each issue also includes useful practice management articles. Canadian Vet Practice is written by our own team of expert medical writers, and is reviewed for accuracy.

Our mission is to be a recognized and credible source of continuous learning to the Canadian veterinary profession by imparting up-to-date information on patient wellness strategies, animal health research, and veterinary practice management topics.

Veterinary clinic access and COVID-19 risks

By Scott Weese, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM

I get a lot of emails about vet clinic access from a wide spectrum of individuals. This includes:

• Owners who are upset they aren’t allowed in the clinic with their pet

• Owners who are upset they aren’t allowed in the clinic with their pet

• Owners who are worried that their vet clinic isn’t doing enough to prevent transmission of COVID-19

• Vets who want to know how to increase owner access to clinics safely

• Vets who want to keep people out of the clinic as much as possible for safety

• (And still some that just yell at me regardless what I say)

There's no "one-size-fits-all" approach to veterinary medicine in the COVID-19 era. I’ve written about different approaches before, but since I get so many questions, here are some more thoughts.

Why can't someone just say, "here's what all vet clinics should do"?

There's too much variation between clinics. This includes things like the degree of COVID-19 activity in the region, local rules, staff and management risk tolerance, clinic size, waiting room and overall clinic layout, exam room numbers and size, and ventilation, among others.

What are the basic concepts of COVID-19 prevention in a clinic?

- Restrict access as much as possible.

- Choreograph movements in the clinic

- Restrict close contact situations, especially in small rooms.

- Use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

1. Restrict access

I've said to keep owners out "as much as possible" in the past. This has led to issues since "as much as possible" is very subjective, but I can't really say more. There's a cost-benefit consideration. Every time someone new comes into a clinic, there's some risk. The more that happens, the more the risk. The better our other control measures are, the lower the risk (i.e. we can get away with more people in the clinic by doing everything else right).

I've said to keep owners out "as much as possible" in the past. This has led to issues since "as much as possible" is very subjective, but I can't really say more. There's a cost-benefit consideration. Every time someone new comes into a clinic, there's some risk. The more that happens, the more the risk. The better our other control measures are, the lower the risk (i.e. we can get away with more people in the clinic by doing everything else right).

We can limit access but still allow some people into clinics, with some preventive measures. There may be logistical reasons to let people in (e.g. owner walks to the clinic and would have to wait outside in -20C weather) or patient care reasons (e.g. something needs to be shown to the owner that can't be done well remotely, euthanasia, patient for which curbside transfer might be risky) that are worth the limited increase in risk. There are many other situations where it's not worth the risk. We can still do a lot with telemedicine, curbside drop offs and hybrid appointments (e.g. telemedicine appointment followed by a drop off for a quick in-clinic procedure like vaccination or blood sampling) where the owner doesn't need to be present.

2. Choreograph movements

I was in a clinic the other day looking at traffic flow, and it's a good exercise to try. It's not usually too hard to come up with a logical flow system that creates one way traffic and avoids mixing of people... if numbers are limited. Minimizing the number of people who come into the clinic helps us optimize other preventive measures in the clinic. In combination with some floor markings, furniture re-arranging, designated direction of movement and designated entry/exit points, we can significantly limit contacts and decrease the risk of virus transmission.

3. Restrict close contact situations

Close contact. Closed spaces with poor ventilation. Droplet generating procedures like talking. Those are the high-risk situations for COVID-19 transmission, and they also happen to describe a vet clinic exam room. Time plays a big role in the amount of risk. Fifteen minutes isn't a magical number, but it’s the one typically used to indicate the time that risk goes up. The smaller the space and the worse the ventilation, the higher the risk and the less time you should spend in it.

All those factors together show how the normal exam room visit needs to be rethought. To me, exam rooms are now "owner waiting spaces." If the owner needs to accompany the animal into the clinic, they check in and are admitted directly to an exam room (again, the number of people in the clinic needs to be limited to some degree for this to work). Vet personnel come in and retrieve the animal, keeping chatting to a minimum, distance to a maximum, and everyone’s masked. A little conversation is fine and is good for patient care and the vet/owner relationship, but it should be distanced and short. The pet is then taken to a treatment area for examination and whatever needs to be done. Vet personnel can pop into the exam room or connect electronically to ask more questions or talk about things. The owner and pet are re-united in the exam room, and a short conversation can be had to explain or demonstrate things. If a demo is needed that requires restraint of the animal, someone from the clinic joins in so the owner does not have to help out, and can maintain distance from staff. (That’s still a potential issue because of the reflexive nature of owners jumping in to help hold, but that just needs some communication to head it off.)

4. Use appropriate PPE

As much as they are annoying, masks are critical. Masks need to be worn for any close contact situation, by owners and clinic personnel alike.

LOTS OF QUESTIONS REMAINLot's of questions remain, I know. I’ll touch on a couple of them here but I'm sure there will be more to follow.

What do we do with the exam room after the owner leaves?

The room is ideally minimally stocked with easy to disinfect surfaces. Routine disinfection, focusing on owner contact surfaces (vs our previous focus on things like the examination table) is straightforward. A sign on the door indicating the room has been disinfected is useful and is good for clients to see.

What about the airspace in the exam room? Can the next person go right in?

That's a tough one. We focus on droplet transmission and direct contact when it comes to SARS-CoV-2, but there is likely some risk from accumulated aerosols in closed spaces with poor ventilation (like an exam room). It's probably limited in time and degree of risk, but we just don't know. Most aerosols settle quickly out of the air so they'll be taken care of with surface disinfection. However, should we leave 1 minute, 2 minutes, 5 minutes, or more between owners? Who knows. There are no recommendations for this kind of precaution in similar human healthcare situations, and I haven’t seen any real evidence of risk. A few minutes between occupancies, with disinfection performed after this brief waiting period, is probably reasonable, based on what we know (especially with good mask compliance, as masks reduce aerosol release).

How important is ventilation in the exam room?

More is better. Looking at how much airflow can be achieved in the clinic is useful, as better ventilation disperses and dilutes any aerosols that may be present. Ventilation rates of less than 3 L/s per person have been suggested as being high risk, and 8-10 L/s per person as being low risk. If you don’t know what your ventilation rate is and can't figure it out, go with the "more is better'" approach. Just some quick thoughts that I'm sure I'll add to soon (and get more questions about).

Source: www.wormsandgermsblog.com Published by the University of Guelph Centre for Public Health and Zoonosis Reprinted with permission

Dr. Scott Weese DVM, DVSc, DACVIM is a veterinary internal medicine specialist and the chief of infection control at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College. He is an expert in infectious and parasitic animal disease, including rabies, tick-borne diseases, antimicrobial resistance and emerging diseases. He is the former Canada Research Chair in Zoonotic Diseases.