Canine lymphoma: happy dogs with lumps

Lymphoma is the most common cancer in dogs affecting the hemolymphatic system. This cancer arises in the lymph nodes, spleen, and bone marrow but may affect any tissue in the body. Dogs with lymphoma are usually middle aged to older, there is no sex predilection, and some breeds are at higher risk than others. The cause of lymphoma is unknown but likely multifactorial including genetic predisposition, possible retrovirus, herbicides, or impaired immune system.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation is variable and often depends on the extent and location of the tumour. The majority of dogs will present with greatly enlarged lymph nodes; these patients are usually asymptomatic thus they are commonly referred to as “happy dogs with lumps”. Approximately 20-40% will show vague/nonspecific clinical signs such as inappetence, lethargy, weight loss, vomiting/diarrhea, fever, coughing, and polyuria/polydipsia.

Diagnostic evaluation and clinical staging

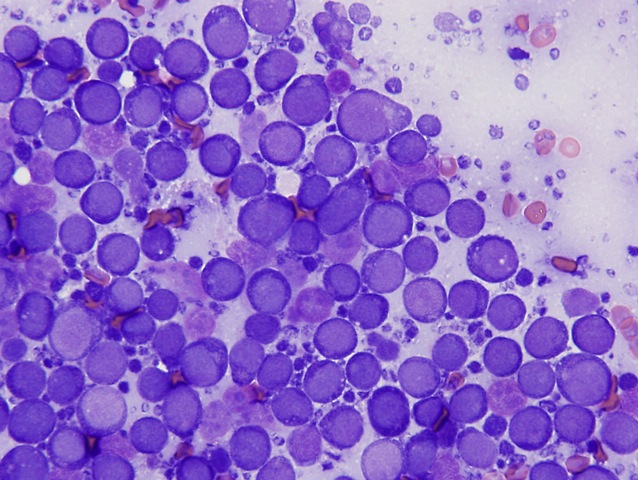

Fine needle aspiration is a non-invasive and inexpensive test that can be easily performed on enlarged lymph nodes. Aspirates can also be taken of the liver and spleen if an abdominal ultrasound is performed. Generally, cytology alone will be sufficient for diagnosis. Under the microscope a homogenous population of large, immature lymphoid cells will be seen (see Figure 1). A biopsy may be necessary if the cytological diagnosis is equivocal. Removal of the entire lymph node is best so the pathologist can fully evaluate the architecture.

Once a diagnosis of lymphoma is made, further staging tests are recommended, including a complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemistry, thoracic radiographs, abdominal ultrasound/radiographs, and bone marrow aspirate.

Figure 1.

Photo credit: credit the picture to Dr. Ryan Dickinson, DVM, DACVP

The complete blood count is often normal but anemia may be present in up to 30% of patients. A leukocytosis may be seen in 30-40% of cases with a stress leukogram being the most common reasons for a neutrophilia and monocytosis. Thrombocytopenia is present in 30-50% of cases but rarely causes bleeding problems.

The blood chemistry is also often normal. If significant liver involvement is present, an increased ALT, ALP, +/- bilirubin may be seen. A paraneoplastic hypercalcemia may be present in 15% of cases. Of these patients, 30-40% will have a mediastinal mass and 35% will have a T-cell lymphoma. Cancer, especially lymphoma, is the most common cause of hypercalcemia in the dog. Hypercalcemia is an oncologic emergency as it may result in azotemia and renal failure if left untreated.

Thoracic radiographic abnormalities are detected in 60-75% of patients with lymphoma. It is important to evaluate the heart as doxorubicin, a cardiotoxic chemotherapy, is part of the lymphoma protocol.

Abdominal radiographs may reveal evidence of sublumbar and/or mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, or liver enlargement. Abdominal ultrasound is highly recommended if clinical signs attributable to abdominal disease are present.

Bone marrow aspiration is important because up to 30-50% of dogs with lymphoma will have bone marrow involvement. This test is indicated for complete staging or in dogs with anemia, lymphocytosis, peripheral lymphocyte atypia, or other peripheral cytopenia.

Treatment options

Treatment recommendations are based on stage, substage, and grade of disease, the patient’s overall health status, the client’s level of comfort with treatment-related side effects, and the time and financial commitment of treatment.

Chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for most cases of multicentric LSA because this is typically a systemic disease. In general, combination chemotherapy protocols are superior in efficacy to single agent protocols. The exception to this is Stage I (localized) disease where surgery and/or radiation therapy may be a viable treatment option. However, the client and clinician must be aware that localized disease can progress to systemic disease and chemotherapy may then be indicated. Chemotherapy protocols incorporate vincristine (Oncovin®), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®), doxorubicin (Adriamycin®), prednisone, and +/-L-asparaginase (Kidrolase®)

Chemotherapy protocols

The University of Wisconsin-Madison 19 week, combination protocol includes the above named drugs without L-asparaginase. Chemotherapy is given once weekly for 4 weeks straight followed by a week of rest and then the cycle is repeated 3 more times. If the patient is in complete remission at week 19, all chemotherapy is discontinued and monthly rechecks are done until the disease relapses. If the patient develops progressive disease while on this (or any) protocol, “rescue” alternatives must be implemented. Most dogs (80-90%) will achieve a complete remission that lasts approximately 8-10 months – this is known as the overall response rate. The median survival time is about 12-14 months with 20-25% of dogs living 2 years or longer.

Single agent doxorubicin (Adriamycin®) is relatively inexpensive and generally well tolerated as it is given once every 3 weeks. Side effects include chemotherapy toxicity, cardiotoxicity, anaphylactic reactions, and extravasation injury. Approximately 50-75% of dogs will have a complete response and a median survival time of 6-8 months.

Non-doxorubicin based protocols (COP) includes cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone. Median survival time is 6-7 months with an overall response rate of 60-70%.

CCNU (Lomustine) is usually reserved as a “rescue” protocol, after a patient has failed one of the above listed protocols. It is given orally and is relatively inexpensive. While gastrointestinal side effects are minimal, CCNU can cause severe myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, and irreversible thrombocytopenia. It is generally not recommended as a first line therapy due to poor median remission times (40 days) and overall survival (110 days).

Prednisone alone can be used as a palliative treatment when owners cannot pursue chemotherapy. Fifty percent of dogs will have a response but remissions are generally short (1-2 months). Owners should be warned that treatment with prednisone might result in multi-drug resistance to traditional chemotherapy, limiting further treatments.

The MDR-1 mutation involves a gene that encodes p-glycoprotein, an important drug transport pump that limits the amount of drug absorbed and distributed throughout the body. Herding breeds with this mutation are at risk for serious chemotherapy toxicities. In these breeds with lymphoma, submitting a sample to the University of Washington for analysis of the mutation is recommended prior to beginning chemotherapy (remember “white feet, don’t treat”). While awaiting results, a non-MDR-1 associated drug, such as cyclophosphamide, can be started out of sequence.

Rescue protocols

Rescue protocols incorporate drugs that have not been used previously in the patient. If the patient relapses a few months after completing the induction protocol, reinduction should be attempted by reintroducing the protocol that was successful initially. If this fails to induce another remission or in the patient that has failed to achieve a complete remission with the initial induction protocol, a rescue protocol would be used. Overall response rates of 40-50% are reported but these responses tend not to be durable with a median response time of 1.5-2.5 months.

Prognosis

Survival times of approximately 12-16 months are generally quoted if the patient has

had a complete response to combination therapy that includes doxorubicin. Dogs with

B-cell lymphoma tend to live longer than dogs with T-cell. Survival times with prednisone

alone are about 2-3 months and if no treatment is given dogs are usually euthanized

within 4-6 weeks. The goal with lymphoma is remission and excellent quality of life as

cures are uncommon.CVT